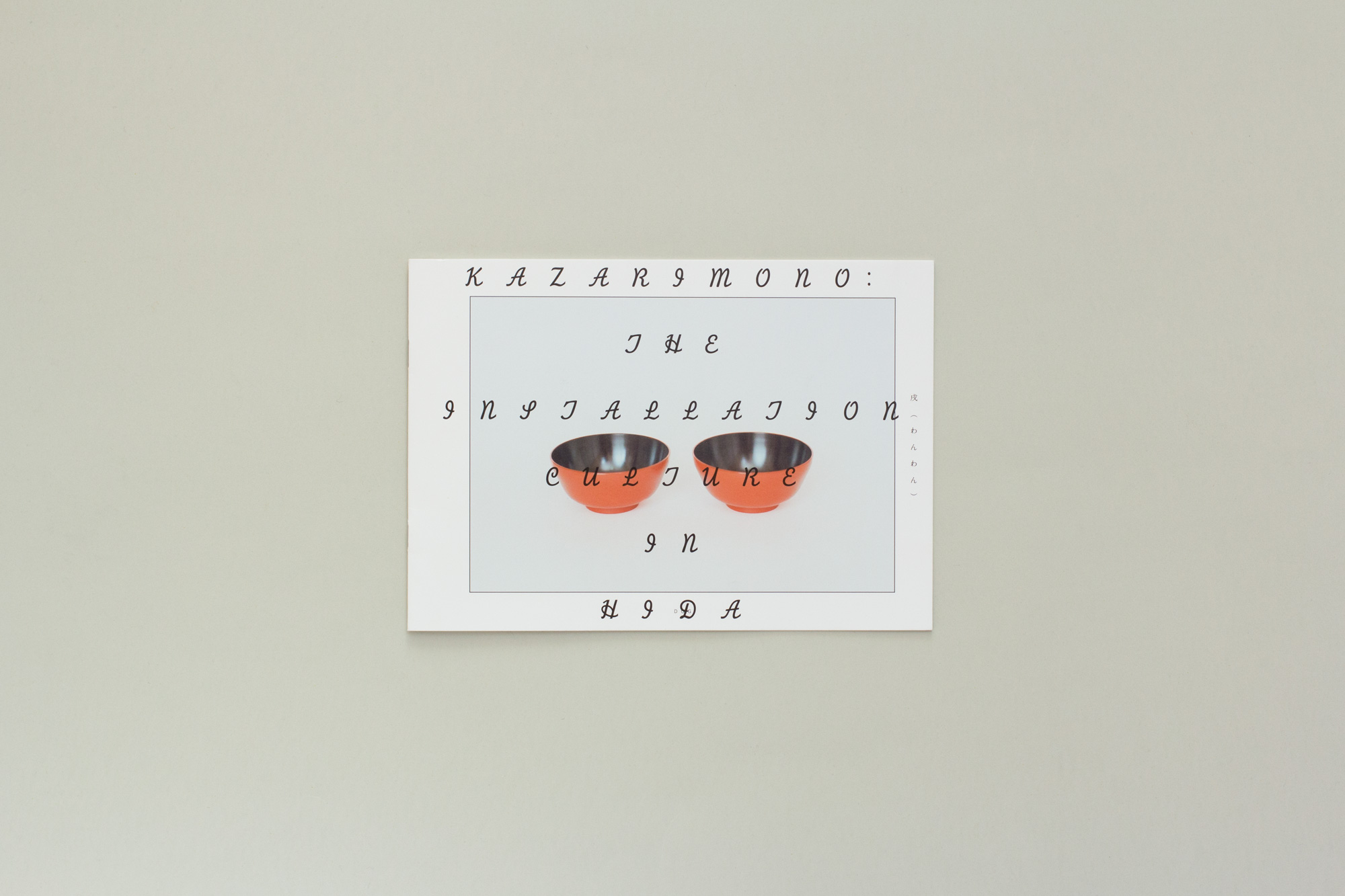

KAZARIMONO: THE INSTALLATION CULTURE IN HIDA

Artist: Sadao Ayutobi

Idea, Design, Writing and Publishing:

Miki Kadokura for The Simple Society

Copyediting: Sophie Perl

Photography: Mutsumi Tabuchi

Supported by: 5+ Published in Oct. 2013

Kazarimono is a witty and refined traditional pastime culture unique to the region of Hida, central Japan. Kazarimono literally meaning “decorative item” is in this case a creative installation usually displaying some kind of riddle or wordplay. The oldest kazarimono on record dates back to 1787 as a votive offering for a shinto shrine in Hida-Takayama. Some suggest that it later evolved into an entertainment at parties of the nobility and the bourgeoisie. From there it turned into a new year’s tradition popular amongst local craftsmen.

Usually a kazarimono poses some kind of riddle whose meaning the audience is supposed to solve by observing the installation. There are three basic types of kazarimono:

1 TSUKURI-MONO: creating an imitation of an object or scene by using other objects

2 HANJI-MONO: a wordplay

3 MITATE-MONO: an object chosen for its resemblance of another object (i.e. pear → lightbulb)

A traditional kazarimono should follow the following rules.

– One installation should be made from one category of ordinary objects, i.e. tea ceremony tools, tableware or carpentering tools.

– The items used must not be cheap or obscene, but should be elegant and precious – something that can be placed in a tokonoma (the ritual alcove in a Japanese house). This means that for example footwear can’t be a kazarimono since the tokonoma is a sacred place and footwear is considered dirty and desacrating.

– The objects should not be too extravagant but preferably simple and beautiful.

Very much like with modern concept art the audience’s wit and thinking are required in order to complete the communicative experience that is kazarimono.

THE MASTER

Sadao AYUTOBI, whose work is presented in this book, is a retired traditional clay wall plasterer, a craft of high regard in Japan. He was born and grew up in Hida-Furukawa where he is widely known as a vivid storyteller. Both his knowledge of local history and his achievements in kazarimono contests are acknowledged by the city and the people. He is very active in passing local traditions including kazarimono to the next generation by frequently giving lectures at primary schools.

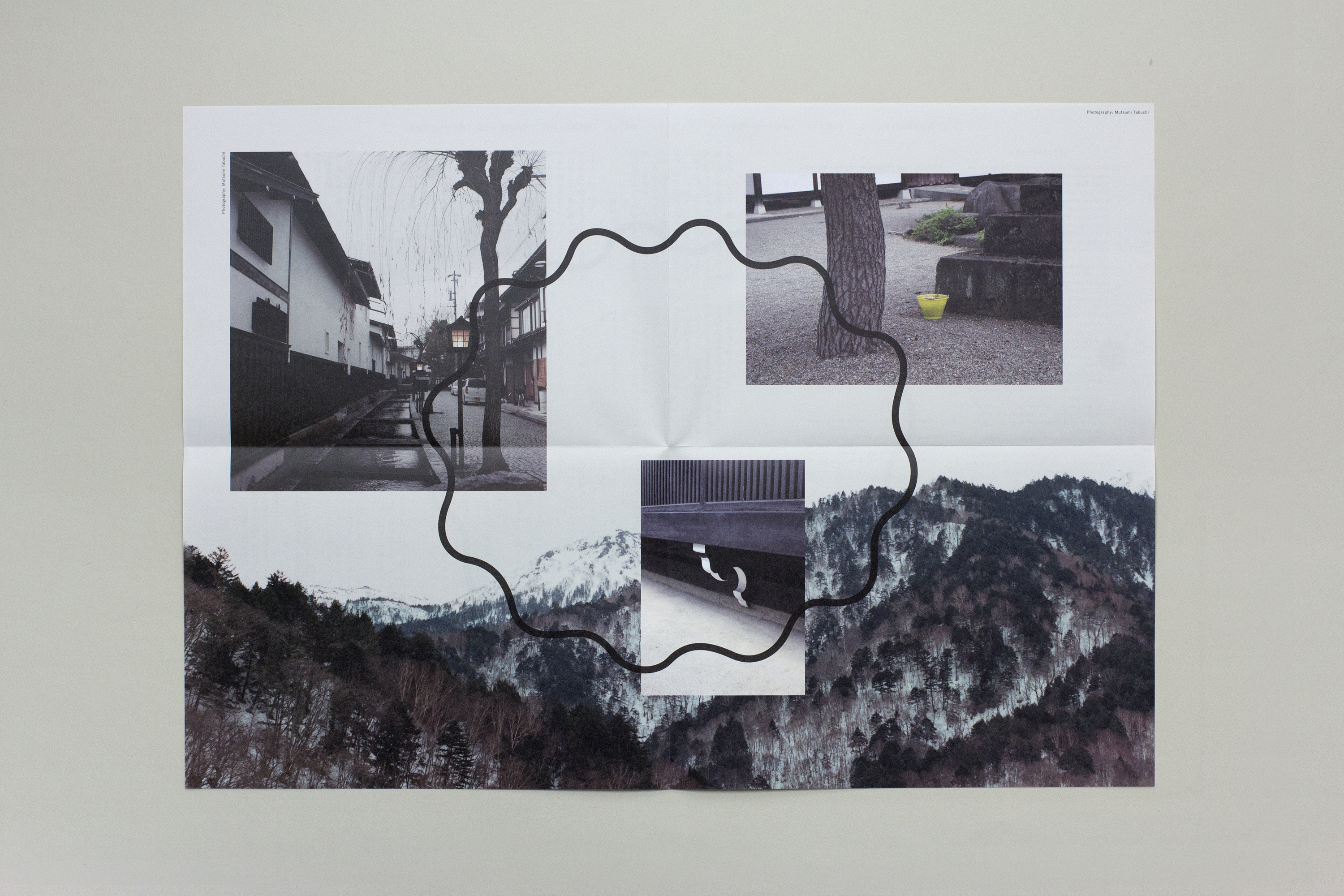

HIDA-FURUKAWA

Hida-Furukawa is a small town in the mountains of the Gifu prefecture that looks back on a long history and has preserved significant parts of it both in every-day traditions and the physical appearance of the city. The people of Furukawa are proud of and active in not only preservation but also the creation of ever new traditions with a high sense for aesthetics and beauty.

KUMO

KUMO (cloud) is the name for a white relief at the end of the black beams that stick out from underneath the roof onto the street side. Furukawa has developed a unique culture around the kumo where every carpenter in town – and there are more than 150 today – has his signature ornament. Since the Nara period (A.D. 710-784) Hida had been known for its carpenters who specialized in building shrines, temples, and palaces. But the kumo craze is actually a rather young tradition. Only after the war (1945) did one carpenter begin to use a unique kumo as his signature and thus started an ongoing competition amongst his peers whose fruits nowadays dominate the city landscape.

THE SETO CANAL

The Seto canal is the lifeline of Furukawa. It’s a small stone embanked canal that runs through the heart of the city and was originally used for irrigation and washing, as a snow dump and for fire fighting. Alongside the canal are located several famous sake breweries housed in large traditional buildings. The canal itself is full of beautiful big koi carps. But this iconic Japanese landscape isn’t as old as one might expect. Furukawa was almost entirely burned to the ground during a big fire in 1904 and hat to be built up again. In the 1960s the pollution of the canal had gotten so serious that the people decided to clean it up once and for all and released 230 kois as a pollution barometer, so to speak. There are an estimated 1000 kois roaming the canal today.

SOBA-KUZUSHI

There is a very peculiar word in the Hida dialect, “soba kuzushi”, literally meaning “disrupting harmony”. The people of Furukawa are very concerned with avoiding soba kuzushi in their lives. This principle might have shaped their aesthetic awareness and may have laid the groundwork for the kazarimono culture.

INTERPRETATION

1 DOG

This is another example of a wordplay. The barking sound of a dog in Japanese is “wan, wan”. The word for bowl is also “wan”. So two bowls equal a dog! This kazarimono is usually Mr. Ayutobi’s opener at primary school lectures. Its simplicity and humor are representative of the ideals of kazarimono.

2 CRANE AND TORTOISE:THE SYMBOL OF THE LONGEVITY

An ogi (fan) as a crane and a kogo (incense container) as a tortoise to depict an ancient symbol of longevity. Both are tools used at the tea ceremony.

3 THE YEAR OF THE BOAR

A chasen is a bamboo whisk used at the tea ceremony. The smaller one being a portable one for outdoor use. The white fan becomes a snowfield on which a family of boars runs uphill. The wild boar farrow is a symbol of the coming spring and its entailing prosperity.

4 THE FROG IN PERIL

A foldable teaspoon representing a snake luring behind a bamboo whisk container and starring at a paralyzed frog represented by a whisk.

5 BUSINESS PROSPERS

This is an example for a hanji-mono using homonyms. The box is a measuring container called masu. The bigger one is for 1 sho (1.8L) and the smaller one is for a han(half)-sho, the syllable bai means double. The solution if this riddle is the classic saying “Sho-bai Masu Masu Han-Sho” meaning “business prospers”.

6 ASCENDING DRAGONS, DESCENDING DRAGONS

A mitate-mono for the year of the dragon. Ascending and descending dragons depicted by using different versions of the kote, a traditional plasterer’s trowel used for the finishing of walls in ceremonial rooms. In classic belief the ascending dragon sends people’s prayers to heaven, the descending dragon comes down to answer.

7 DEPARTURE

A family of ducks moving quietly on the water depicted by using eight tiny trowels, normally used for the finishing of corners and edges of clay walls. The swimming formation of the ducks resemble the shape of a family tree and thus symbolizes fertility.

8 THE LITTLE WARRIOR IN A BOAT

“KISHI (shore)” was the theme of the 2012 new year’s haiku gathering at the imperial court. This mitate-mono had something to do with it. There is an old fairy-tale called Issun-Boshi (comparable to Tom Thumb). He goes to Kyoto in a boat made out of a bowl and a paddle made out of a chopstick. In Mr. Ayutobi’s kazarimono take on the story, a black thread of a tea whisk turns into the belt of a hakama (formal wide trousers).

9 LIONS DANCE

A fuchin is a hanging weight to keep a kakejiku (scroll) stable in the wind. This mitate-mono uses a fuchin as the traditional lion mask which is used for a dance called shishimai.

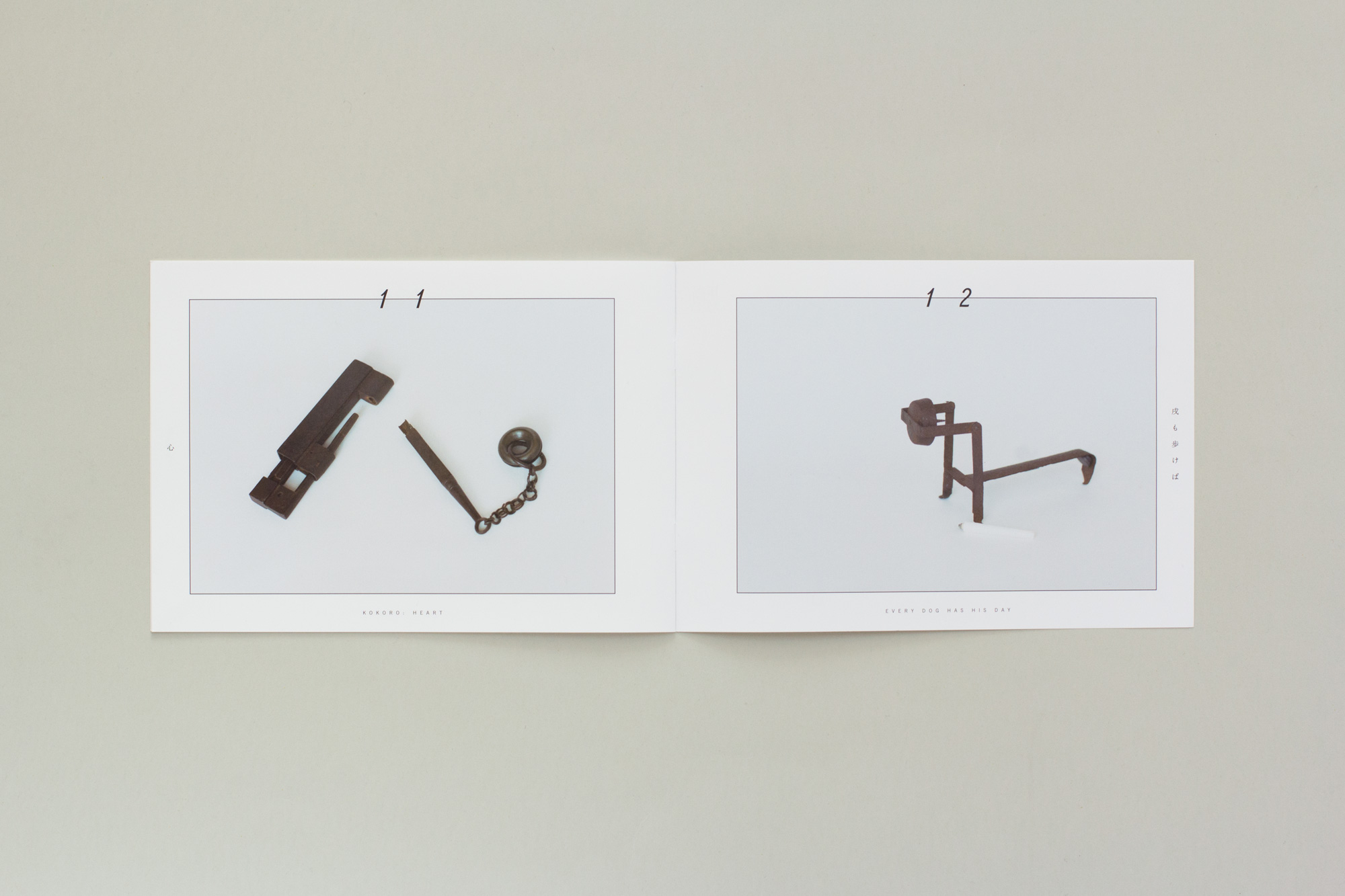

10 KOKORO: HEART

This antique key from the Edo-period (1603-1868) laid out in a certain way resembles the Chinese character “kokoro” (heart). This kazarimono was made in the year of the city council elections and was intended as a witty message for the often bullheaded electorate: “open your hearts (minds)”.

11 EVERY DOG HAS HIS DAY

MITATE-MONO for the year of the dog by using a portable candleholder. Originally the round part is where the candle stands while the whole apparatus is hanged on the kamoi (lintel).

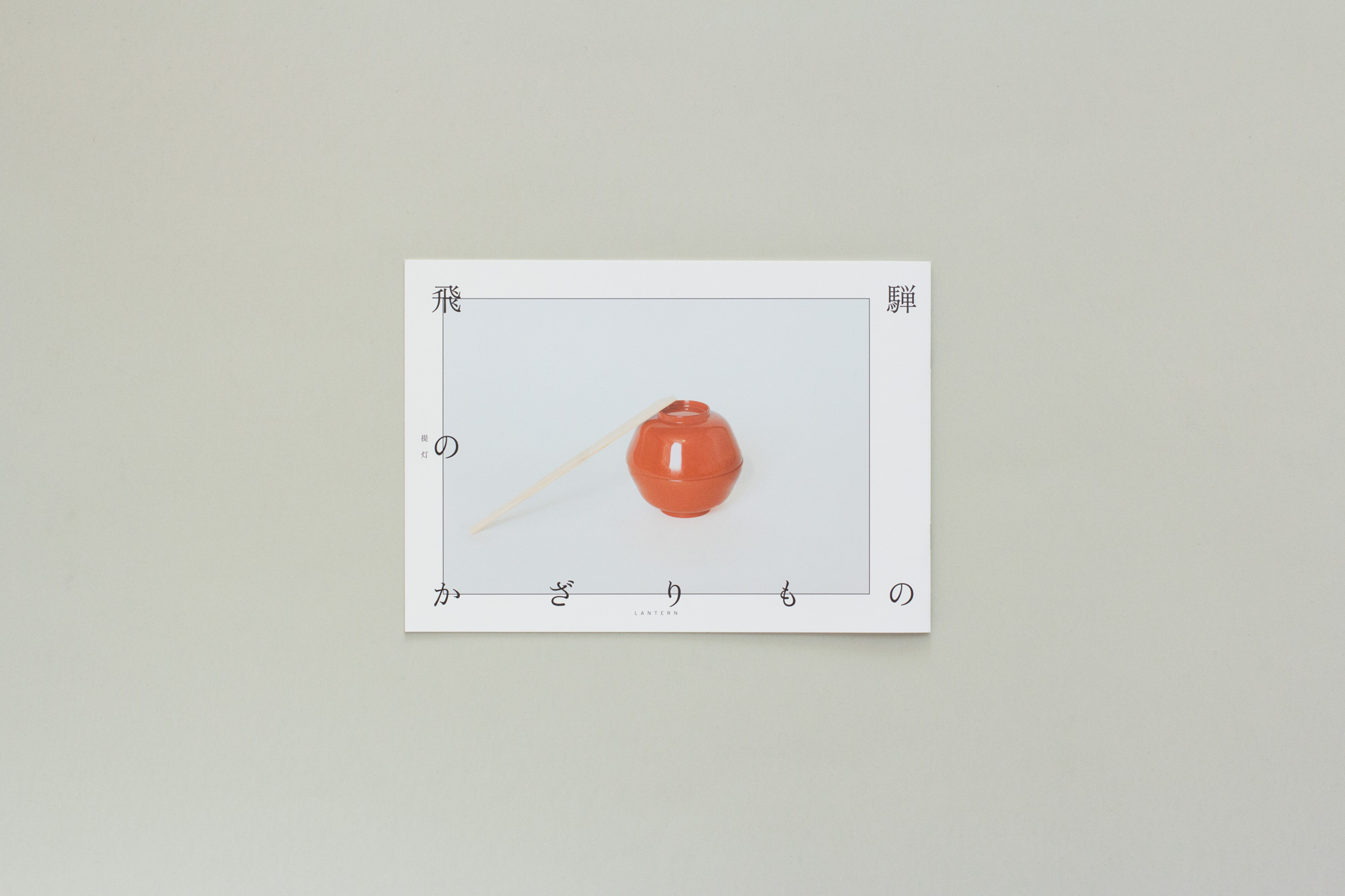

12 LANTERN

A tsukuri-mono using two lacquer bowls on top of each other as a lantern and chopsticks as its handle. This kazarimono is displayed at the Furukawa festival in January where a lantern parade is considered the highlight.

飛騨のかざりもの

立案・取材執筆・デザイン:門倉未来(シンプル組合)

飾手:鮎飛定男

写真:田渕睦深

英訳監修:ソフィ・パール

協力:5+(ごとう)

著者・翻訳・装丁・出版:シンプル組合

発行:2013年10月

飛騨の飾り物

一七八七年、高山郡代大原正純が陣屋稲荷の初午祭に「二十四孝」の飾り物を奉納したのが最も古い記録とされるが、旦那衆が始めた余興ともいわれる「こうと(地味で上品という意味の飛騨弁)」な町人文化である。今では、高山や古川など飛騨地方を中心に、新年など祝事の際に、民家の軒先で出格子を外し緋毛氈を敷き、銀屏風を立て「飾り物」を展示する。本物に似せた「作り物」、とんちの利いた「判じ物」、物を何かに見立てる「見立て物」の三種の飾り方がある。道具は、茶道具、酒器、大工道具など、同系統でまとめ、生活の道具でありながらも、床の間に飾れるような品のある道具を選ぶことが求められる。豪奢でなく、ごく自然にありのままの姿で飾るのを良とする。また飾り手の洒脱さは勿論、見る者にも知的感度が求められる。

名人、鮎飛定男

本書の飾り物の飾り手、鮎飛氏(七七)は飛騨古川で左官業を営む飛騨の匠の一人。左官業の傍ら、語り部として、観光客の案内をはじめ今に至る。先代から受け継いだ貴重な左官道具や、自慢の骨董品を用いた氏の飾り物は、毎年高い評価を受けている。また、地元の子供たちに飾り物の魅力を伝えるため小学校で講演するなど、文化継承にも力を入れている。

飛騨古川

鮎飛氏が暮らす飛騨古川は、司馬遼太郎が「飛騨随一ノ町並也」と謳った美しい風景で有名である。古川の特色は、単に伝統を守るだけではなく、代々培われてきた高い生活感への美意識により「日々の暮らしに活きる伝統を新たに生みだす」ところにあると言える。 例えば町家の軒下、出桁を支える小腕(腕木の化粧材)に施された白い彫刻はその形から「雲」と呼ばれ、古川大工の誇り、美意識の高さの象徴といえる。奈良時代から匠の里として知られた飛騨古川には今も一五〇人以上の大工や職人がおり、一人ひとり異なる雲の意匠を持つ。しかしその歴史は比較的新しく、戦後に一人の大工が取り入れたものが広まったとされる。また瀬戸川沿いに連なる造り酒屋の白壁土蔵、この美しい町並みは、一九〇四年の大火で全町のほとんど焼失したところから、旦那衆や大工、住民の力でいち早く復興されたものである。また瀬戸川は農業・防火・生活用水の他、冬は除雪した雪を流すための流雪溝として、夏場は鯉が泳ぐ名所だが、高度成長期には汚染が問題視された。しかし一九六八年に一部の町民が住民、企業などから寄付を募り二三〇匹の鯉を放流。これを水質の指針とし、住民が地道に日々の暮らしを見直してきたことで、約千匹の鯉が泳ぐ今の姿に蘇った。

相場くずし

古川には、景観との調和(相場)を大切にし、それを崩すこと(相場くずし)を嫌う気質があったという。これが、生活感がある風情ある町並みを育む美意識へ繋がっているといえる。こうした「暮らしの中の美意識」が、飾り物のような洗練された文化を地域に育んできたのではないだろうか。

解説

○和表紙…提灯

飾り物を見る貴重な機会でもある、新年の古川祭につきものなのが提灯行列。お椀を重ねて箸を添えることで提灯を表現した見立て物。

○英表紙…戌

「椀がふたつで何と解く?」

「わんわん」。

これは鮎飛氏が、小学校で子供たちに最初に見せる判じ物である。

③ 鶴亀

茶道具の扇子を鶴に、万年茸を表した香合を亀に見立てている。

④ 亥雪原を駆る

亥年にちなみ、茶道具の扇子と大小の茶筅を用いた見立て物。野点用の小さな茶筅は新春を想起させる瓜坊主を、扇子は雪山を表している。

⑤ にらまれた蛙

蛙に見立てた野点用の携帯茶筅。それを納める筒の後ろには、蛇に見立てた折りたたみ式の茶杓が鎌首をあげる。

⑥ 商売益々繁盛

一升マスと五合︱︱つまり半升マス(はんじょう)を並べた判じ物。骨董品の升には、縁起をかつぐ大黒様の小槌。

⑦ 辰

辰年にちなみ、左官の細工鏝(こて)六つを組み合わせ、昇竜降竜を表した作り物。これらの鏝は、茶室の縁など非常に細かい仕上げに使うもの。

⑧ 旅立ち

細工鏝八つを組み合わせ、鴨の親子が悠々と水面をゆく様を表している。末広がりの「八」という数は、旅立ちの題にふさわしい。

⑨ 船出

年頭の宮中歌会始の儀、二〇一二年の題「岸」にちなんだ見立て物。京へ上るべく岸を発つ一寸法師を、茶道具で表した。茶筅の黒い糸が段々と袴の帯に見えてくる。御伽草子ではお椀のお舟だが、ここでは茶道具で揃えるために茶器を用いた。

⑩ 連獅子

掛軸が風で翻らぬよう軸先に付ける錘、風鎮を用いた見立て物。しばらく眺めてみると不思議と獅子の躍動が伝わってくる。

⑪ 心

江戸時代の錠前を使った判じ物。飛騨市市長選の年にちなみ「派閥争いをしたり、言いたい事を言わなかったり、陰口を言わずに、心の錠を外した世の中にしよう」との市民への伝言。

⑫ 戌も歩けば

戌年にちなみ、自在蝋燭立を用いた見立て物。普段は丸い皿の部分に蝋燭をたて、鴨居などに掛けて使うが、こうして視点を変えて別の物を見いだすのも飾り手の知恵の見せ所である。